by Kylee Boyter and Vicki Clarke

kboyter@cherryroad.com

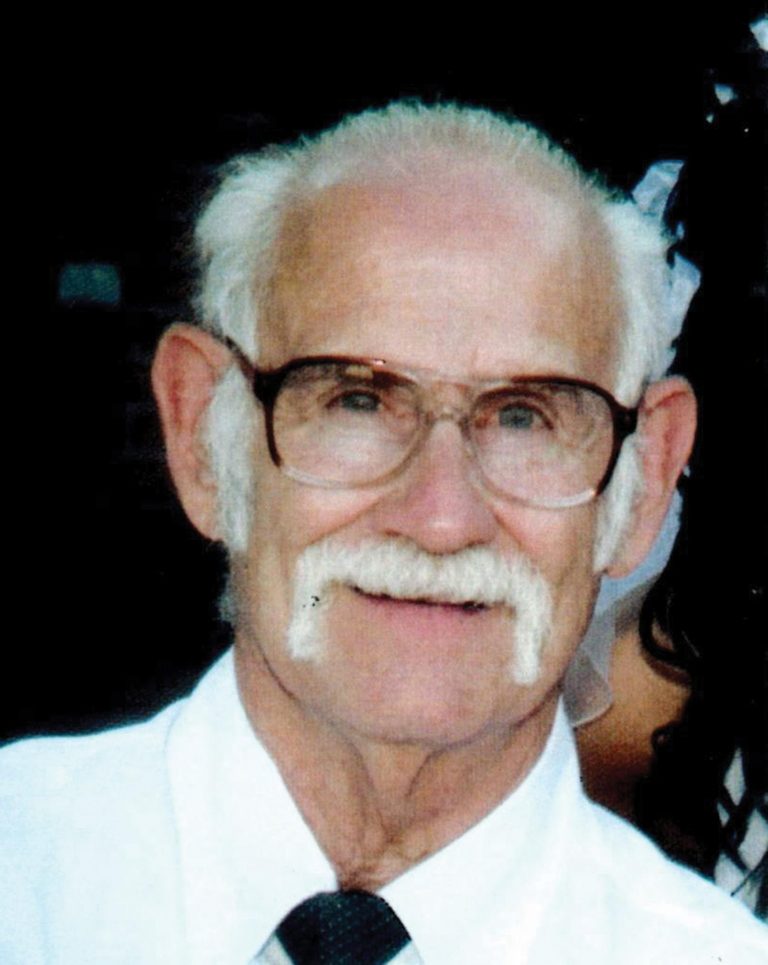

John DeVere Stewart, a former Aurora resident and graduate of North Sevier High School, exemplified how determination and community support can propel someone to extraordinary achievements.

Despite losing his father at the age of 16, Stewart went on to have an exceptional career, serving as one of three test controllers at the Nevada Test Site (NTS), where he played a critical role in ensuring the safe execution of nuclear testing. Stewart passed away last week at 89, leaving behind a legacy of resilience and impact.

In 1951, Stewart’s father, John Riley Stewart, tragically died after suffering a heart attack while working at the SUFCO Mine in Salina Canyon. Known for his remarkable strength, John Riley had taken on the dangerous task of single-handedly turning coal carts for a two-man wage. On the day of his death, he managed to stop an approaching cart and ride it out of the mine before passing away the next morning. This left his wife and seven children, the youngest just a toddler, to navigate life without him.

The Aurora community rallied around the grieving family, and the teachers and staff at North Sevier High School played a pivotal role in supporting the Stewart children.

This support extended to Gordon, Stewart’s older brother, who was encouraged to pursue his academic potential. Gordon became a physics professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Between Gordon’s support and the encouragement from a high school science teacher, Stewart began to see his potential in the academic world.

With Gordon’s help, Stewart earned the Knights of Columbus scholarship, which enabled him to attend Utah State University, where he studied Soil Science.

From there, he embarked on a journey that took him to General Electric at the Hanford Nuclear Plant where he began his remarkable career.

Later to continue to a graduate program at UCLA, Stewart began researching how to reduce the amount of isotopes in the human food chain. The papers he wrote on the subject were published internationally.

Eventually, he joined the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory at the Nevada Test Site, where his work as a radiochemist and health physicist was instrumental in numerous nuclear tests.

Stewart’s contributions were vast. He established and supervised radiochemical and mobile laboratory operations, advised on health physics for nuclear tests, and worked on groundbreaking radiochemistry programs. Notably, he served as the test controller for the last atomic bomb detonated at the Nevada Test Site in 1992.

His daughter, Vicki Clarke, expressed pride in her father’s role in ending nuclear testing in the United States and his efforts to protect the underground Amargosa River system. Stewart’s work contributed to significant advancements in quantum mechanics, which underpin modern technologies such as lasers, transistors, MRIs, and cell phones.

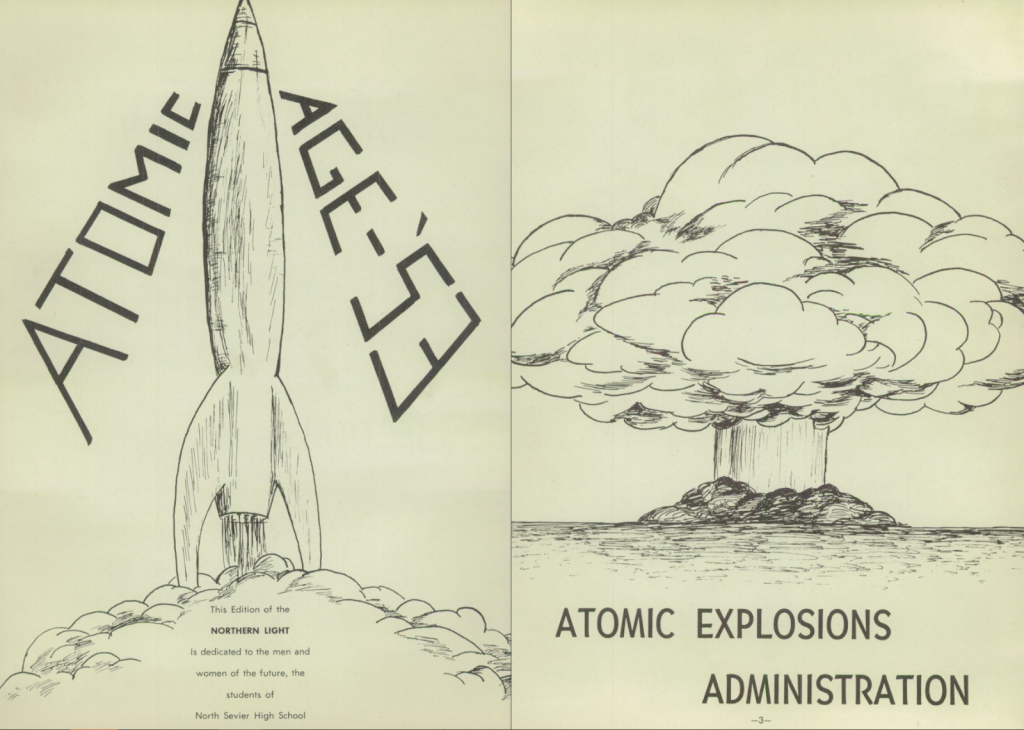

The 1953 North Sevier High School yearbook, dedicated to the “Atomic Age,” unknowingly foreshadowed the pivotal role Stewart would play in this era.

“This edition of the Northern Light is dedicated to the men and women of the future, the students of North Sevier High School,” it stated—a sentiment that Stewart embodied throughout his life.

Stewart’s story serves as a powerful reminder of how one individual, shaped by their community and determined to overcome adversity, can leave an indelible mark on the world. His life is a testament to the idea that our backgrounds do not define our potential, but our drive and the encouragement of others do.